November 24th, 2021, 12:00 pm PT / Category: Interviews

Why food data is the key to unlocking efficiency and sustainability in the food system.

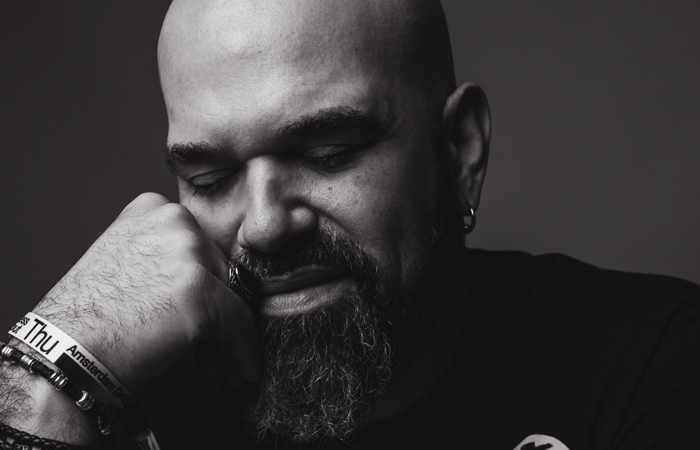

Benji Koltai is the Co-Founder and CEO of Galley Solutions. He is a passionate problem solver, no matter the domain. He has spent his career mastering the craft of problem-solving, using technology. He strives to find and implement simple, creative, and elegant solutions to complex and meaningful problems.

At Galley, Benji serves as CEO and Chief Problem Solver, leveraging his deep experience in food tech to help create a better way of producing food.

Podcast

Transcript

Tullio Siragusa: Good afternoon, everyone. Welcome back to another episode of dojo.live. Today is Wednesday, November 24th, 2021. I’m Tullio Siragusa broadcasting from Southern California. And today joining me are Carlos Ponce in Cuernavaca, Mexico and Kim Lantis in Hermosillo, Mexico. Hi guys, welcome back. This is the last show for this week as we go into a long holiday weekend and we’re excited to have our guest today, who is the Co-Founder and CEO at Galley, Benji Koltai. Thanks for joining us, Benji, we appreciate it. We’re going to talk about food today, we’re going to talk about food and data.

Kim Lantis: Which is quite fitting considering tomorrow is Thanksgiving!

Tullio Siragusa: Exactly. Plus just around the corner from lunchtime. But before we dive into all these great things to unpack and learn, let’s get to know our guest a little bit. Benji, if you could please introduce yourself we’d appreciate it. Thank you.

Benji Koltai: Sure. Well, first of all, thank you all for having me. I’m really excited for the conversation today. So I’m Benji Koltai, CEO of Galley. I am a software engineer, went to school and got a computer science degree and, sort of by happen chance I’ve found myself as an entrepreneur. First time entrepreneur, first time CEO, running this incredible company called Galley. I live in San Diego and have a family here. I have a two year old son and a dog. I have really been enjoying Southern California and surfing and just hanging out in the beautiful weather. It’s a great place to start a company. Prior to starting Galley I was up in San Francisco where I worked for a couple Silicon Valley companies. And then my previous company was sort of the genesis of Galley.

Tullio Siragusa: Nice. Silicon Valley versus Silicon Beach. We’ll take the beach any day.

Benji Koltai: Yeah, exactly! It’s a good place to start a company.

Tullio Siragusa: Tell us a little bit about Galley, what gave birth to this idea? What is it that you guys do?

Benji Koltai: Yeah. So as I mentioned, I’m a software engineer. My last job I joined the company as one of the early engineers. The company was called Sprig and Sprig was started in 2013 and was one of the first full stack virtual kitchens. So that’s sort of a mouthful and I’ll break it down a little bit. So a virtual kitchen, I’m sure people are familiar with those by now. You’ve probably eaten food from a virtual kitchen at this point, especially in the pandemic with COVID and having delivery being such an important part of how people eat. The idea of a virtual kitchen is that it is delivery food that’s made in a facility that doesn’t really have a storefront. You can’t walk up and order that food. You can only order it on the delivery platforms, on delivery apps like Uber Eats and Postmates and DoorDash.

So before those platforms existed, the founders of Sprig had the idea that people wanted to use their phones to order food and have it delivered to them. Because that infrastructure didn’t exist, we had to build the full stack. So we had to have a customer app, make our food and deliver that food, all under one company with one cohesive team and technology stack. And so I got a unique experience to see sort of the early beginnings of what is now becoming the future of food, this technology driven delivery food process. And I got to see how technology was improving the consumer interaction that is online ordering, mobile ordering, and also the delivery experience. The drivers had their own customer custom driver app. There was smart logistics that literally could deliver your food in two minutes was the Sprig model.

That was pretty incredible. And then there was the kitchen component, which was left almost entirely in the dust in terms of technology. And I saw how that became a bottleneck for technology adoption in this sort of digitally driven value proposition. Essentially kitchens don’t have much software built for them to help them run more efficiently. Most kitchens of any size or any kind are run on spreadsheets or manually. And that was the case at Sprig. When I looked at the kitchen, they were running it on spreadsheets and that was causing issues for the consumer. You know, recipes were mislabeled, dishes were mislabeled. I was gluten-free. And so it was important for me to have a clear label that says, yes, I can eat this, or no, I can’t. And I couldn’t rely on it because it was being managed by a human.

And I said, “Well, why aren’t we just plugging into the recipe database?” They said, “What recipe database? It’s a spreadsheet.” And so I just started building software to solve that. I first built software to manage the recipes, and then it quickly evolved into production planning, inventory management, purchasing, and essentially all the pieces that anybody who makes food, even a home cook, you don’t have to be a professional kitchen. These core components are true anytime you make food. And so I built the system at Sprig. It solved Sprig’s problem. People who used it at Sprig said, “Hey, this would have been life-changing at my XYZ last job. Please make it available even if Sprig doesn’t make it.” And so in 2017, unfortunately, Sprig shut down. And that was my opportunity to take this system and the learnings that I had made in building that V1 of the system, throw it all in the trash, start from scratch, rebuild, brand new, fix a lot of the mistakes I made. And now we have Galley in year four after starting it towards the end of 2017.

Tullio Siragusa: Awesome. Okay. So let’s see if I can – I like to break things down to very simple terms. So you’re basically like a resource planning or the equivalent of an ERP for kitchens. Is that an over simplification?

Benji Koltai: That’s a very good simplification.

Tullio Siragusa: Awesome. Okay. Let’s see what we can learn today cause this is very interesting. Made me think about a lot of possibilities. Carlos, please, if you could introduce the topic today. And Carlos is back.

Carlos Ponce: That is back.

Tullio Siragusa: We missed you being on mute. It’s been a long time.

Carlos Ponce: I miss my trademark. So before we went on vacation, I said, “I’m going to remind them of who I really am.” I am known as the mute guy. Okay. Well, thank you Benji for being with us today. And as you can see, we’re a bunch of clowns. We’re about to have fun. But you’re talking about really interesting and important stuff like food data. So we’re going to be answering your question. The question is “Why food data is the key to unlocking efficiency and sustainability in the food system.” So the topic as chosen by our guest today is “Recipes: the Center of the Food System.” Benji, tell us, why did you choose this particular topic and why did you feel that it was relevant for today’s day and age?

Benji Koltai: Yeah. Well, I picked this topic because it’s been sort of my life’s work for the last, you know, seven years now since I encountered this first at Sprig. And as I’ve worked on it more and more, I’ve become more and more convicted with this simple idea, that has global sort of impact and an influence in that, if you look at the food system, if you look at what is the food system. So in my mind, when I say food system, I think of farming, sort of food production, you know, raising animals, planting, you know, producing the food that feeds the world. It goes through a supply chain to get to kitchens, whether those are home kitchens or commercial kitchens. And then it goes through now another logistics chain of delivery and getting handed off to those end consumers.

And sometimes that piece doesn’t exist. Sometimes you’re consuming it in your own kitchen, like when you’re at home. But sometimes it has a complex sort of flow and we’re even seeing it become more complex with organizations where they’re creating sauces in one facility and transferring those to another facility so that it’s closer to the homes that they’re serving. So there’s these multi-chain pieces of production. So it’s becoming more and more complex to execute food. And when you look at that whole system, the underlying single sort of piece of data that drives all of that activity – is a recipe. Why do farmers plant things in the ground? Because of the recipes that the culture creates in those regions or globally now, right? Food is now a global thing. We’re moving ingredients across the globe all the time. And all of that is driven by what’s being made. How are those ingredients being put together into dishes that people are eating?

Carlos Ponce: So is it some kind of like reverse engineering of the food world, like you’re going –

Benji Koltai: Yeah, kind of, yeah. I love, you know, I can’t remember who it was, but there’s this quote that’s like, “The brilliance or genius is about taking complex things and simplifying them.” And so to me, I love that this simplifies this really complex system to say, “Hey, it’s all just a recipe.” Everything comes down to a recipe. And if you can then fix that, if you can focus on that, and you can really structure it well and digitize that, the possibilities of what you can do with that core data, the branches that you can take are essentially endless. And I really saw this, you know, again, from my intro, like my pain coming in and being a consumer of Sprig was first experienced by that recipe data being wrong. It wasn’t correctly labeled in the customer app. And I was a consumer that really cared about dietary flags and allergens.

And so that single piece of data, once I structured it, really unlocked automation in the kitchen operation. And then eventually, you know, to speak to the other pieces of the topic that I asked to talk about – efficiency and sustainability. I think those are really key, especially, you know, the last couple of weeks, talking about the sustainability of the food system. How do we reduce the waste? How do we better utilize all of the resources that go into making food? And how do we better match the demand and supply of the global food system so that everybody can have plenty of food to eat? You know, how can we sort of solve that waste problem so that everybody can eat?

Carlos Ponce: Reminds me of a conversation we had recently precisely around the topic of food, but specifically about the management of food waste and how to either avoid it or reduce it, or even get rid of it altogether. Right?

Kim Lantis: I was thinking that too. It was this Stefan Kalb at Shelf Engine, specifically for grocers and their fresh produce, what they’ve got in the delis and things like that. And with their technology they’ve got it backed so high that if they’re wrong, they’ll pay you back for anything that goes to waste.

Tullio Siragusa: Yeah, that goes to waste. I mean, it’s so reminiscent of, I find it fascinating. We take so much for granted. If you’re in technology or in manufacturing, we’ve had supply chain systems that have evolved over decades. Now we have just-in-time supply chain system, that everything is interwoven and linked where the minute there’s a component that’s pushing, it automatically places an order for more components. And it’s tied to the demand system. Everything is talking to each other to keep that workflow efficiently operating. But when it comes to food and restaurants, it’s all manual. I mean, you just, you know, how do you keep up with a dish that’s in higher demand this week that required certain ingredients that you’ve run out in the kitchen? Someone has to keep a tab on that and then go out and shop for it. So let’s see if I get this correctly. What you guys are doing is automating all that. So that there’s a supply chain set up in terms of how the restaurant supports the dishes that are being purchased by the consumer. And also making sure that the supply chain is aligned. How does that work with the farms and the producers of the ingredients that may not be automated yet? Does it also extend the same capability to disrupt how they typically do things? How does that come together as an ecosystem?

Benji Koltai: Yeah. So first of all, I just want to sort of reinforce what you’re saying. Just-in-time logistics is absolutely what we’re working towards and automating purchasing; automating that supply chain is exactly what we’re driving towards. The food industry is a lot harder than the manufacturing industry, because the widgets expire. A screw does not spoil. A nut does not spoil. A sheet of aluminum. I mean sure, in a long enough time span, but tomatoes last three days, right? And so it’s even more critical to think about the supply chain. So the other aspect that’s unique in the food system is that there’s this, because each widget, each component expires, there’s this health and safety sort of regulation around food handling and food storage. And right now, every kitchen is a unique silo because I have a individual relationship with my supplier who sends me ingredients.

And those ingredients will never leave my kitchen until they go out my door and get served to my customers. And a lot of that is because of the expiration time on those ingredients and the safety concerns of like, “Hey, I can’t transfer this unit to another kitchen.” Even if I have way too much, I made a mistake, they over-delivered, I over purchased… and now I have an extra three cases that are not yet spoiled, but I know will spoil. I can’t offload those in a very good way. Now, there are a lot of companies starting to upcycle that and try to handle that. And so what I’m trying to get to, in your question, is expanding the definition of supply chain. Yes, right now all food that goes to a kitchen comes from a farm, but that’s because there are certain constraints in play where you don’t have full traceability.

So it’s not safe to do peer-to-peer transfers and you don’t have the sophistication that can instantaneously and accurately say, “I need to move this tomato from this kitchen to this other kitchen.” So when you have a centralized system that is Galley, that knows the state of everybody’s kitchen and not only their current state, but their future state – because we know their plan. We know the orders that have been placed. We know what’s going to get delivered. We can flag ingredients to say, “Hey, this is not allocated to be consumed before it’s expected to expire. Here are the top five ways that you can mitigate that expiration. You can send it to another location and maybe resell it for 50% of the costs. You can offload it into a non-profit organization and here’s the sort of certificate of its safety health-wise so that that becomes a safe thing and allowed thing to do.” So the possibilities of changing the supply chain to support this just – you can’t just constrain yourself to the current supply chain. If you’re going to have just-in-time logistics in this space, you have to also remove the constraints of what it is to be a supply chain and sort of redefining the supply chain as well.

Kim Lantis: It’s crazy, like tapping into an entirely new network of local restaurants. Which kind of, I think, goes really in line with – culturally speaking – what we’re trying to do, right? Shift away from franchises and monopolies and into this more friendly neighborhood mom and pop…

Benji Koltai: Micro. Local. Micro. And even when you think about micro farming, indoor farming, right? So in the near future, we’re going to have a sort of made-to-order shipping container farm that a neighborhood or a group of food businesses can order. And it will have five rows of lettuce, 10 rows of strawberries and whatever else you want. And that will just be plopped down right next to you. So understanding what the parameters are for those and how to best order those so that its services the recipes in your region and creating completely new supply chains where you’re getting all of your greens from the indoor farm right next door.

Kim Lantis: Getting even more micro, going back to your genesis story of your own, the each individual restaurants’ or food suppliers’ recipes. Is it gluten-free? Is it not? Is your food data also not just on the supply chain aspect but with the actual food itself? I mean, what sugar content does a blueberry have, or I don’t know? And then does that also lead to creativity and efficiency inside the organization? Meaning, okay, these tomatoes are going to expire. What recipes require a cooked tomato? Or can I stew them? Or, I don’t have chia, but I have, what’s a substitute? I don’t know – that still kind of fits in with the culinary needs.

Benji Koltai: Exactly. Yeah.

Tullio Siragusa: So Kim wants to turn everybody in the kitchen into trained chefs.

Benji Koltai: Yeah. Well, you might as well leverage the data and get serious suggestions on what dishes you can swap out because the price of chicken just went up seven X because there’s a pandemic and there’s a global supply chain issue. Automatically have a system that looks at not only your recipe catalog but says, “Hey, here are dishes that have similar flavor profiles, have a similar sort of position on a menu.” Right? Cause as a restaurateur, you think about, “I want this kind of dish and I want that kind of dish so that I can have a well-rounded menu.” How can you start to apply data and recipe data to help automate and drive and service those recommendations? And even as you’re saying, “Hey, you have a gap in your recipe catalog. There’s this substitution that you can make where you can have sweet potato instead of russet potato. And when you do that, you should add a little bit more fat and, you know, here’s a sort of guided way to make a new dish,” if you’re an organization. So that is a perfect example of why not only what we do in terms of making kitchens more efficient is really important, but the data that we’re collecting and the ways that we’re going to be able to aggregate, obviously anonymize – protect IP is a big thing for our customers of, “Hey, I have this proprietary recipe. I don’t want you sharing that with other people.” That’s not what we have, what we would do necessarily, but we can say, “Hey, here’s some ideas that we’ve seen in a hundred of the recipes that we have.”

Carlos Ponce: I can see very easily how that would benefit not just at the household level, the families and such, but also the restaurant industry, whether it be directly to the consumer, to the patrons or even at the, even more so I would say, at the industrial level. Do you know, do these large – how do you call those, the places where people gather to eat or have lunch in factories –

Benji Koltai: Food halls.

Carlos Ponce: Food halls, exactly. So I can see the benefit of maintaining a balance of using all of this data to keep everything pretty much flowing smoothly and seamlessly without many disruptions. Am I right?

Benji Koltai: Absolutely. Yeah. A hundred percent.

Tullio Siragusa: I mean, Benji, dare I say, I don’t want to get all political about this, but dare I say, this has societal impact as well? As I’m listening, I can’t stop but think, “Why isn’t the FDA pushing for this kind of movement?” Because there’s so much waste that happens out there. Hunger is actually a logistical problem. It’s not a real problem. There’s so much waste that could be solved by just collaborating, having a system like this, which would allow more interaction and the ability to really manage the supply chain and make it go where it needs to go before it goes to waste. Is there any thought to this becoming something that gets more regulated and required in the food industry, as a way to help reduce number one, waste, but also kind of help with the hunger issue that’s happening out there that doesn’t need to be happening? Any thoughts around that? I mean, is that too big of an idea?

Benji Koltai: Oh no. I mean, we’re already working with these government organizations who put out grants for initiatives that can reduce food waste. So last year we worked with CalRecycle here in California and they had a grant for reducing food waste and we were awarded that grant and we were able to use some of that grant money to build out specific features that would just continue to help our platform reduce that food waste. So I think that there is absolutely a governmental sort of large organizational drive to help solve this problem. And the more and more we talk about, and that’s why I wanted to talk about it here, of the importance of sustainability in the food system and our combating of climate change ultimately. It is a huge component of climate change and technologies like this that really fundamentally change how people do things is what is going to unlock, really, the savings that we need as a human race, as a global society, to get this problem under control and fix these logistics.

Benji Koltai: The other thing that I wanted to say around regulation is that regulation sort of this interesting catch 22 where it tries to be right at the cutting edge of what is possible and you can only really regulate things that people have a chance of adhering to, but you can’t be 10 steps ahead. So does the FDA actually want to regulate more stringently food safety and food tracking, such that if there’s a salmonella outbreak, they can send a text message to everybody who they know ate the contaminated batch that came from the supply chain. Like that sort of stuff would be amazing. We just don’t have the technology for it yet. So my thought is, is it the technology that comes first that leads to the regulation because the technology makes the regulation available and then it catalyzes the adoption of the technology? That’s what I see. And so as we create the technology, the possibility to provide that farm-to-fork trackability, traceability of that onion, that specific ingredient, the regulation is then going to fall on and be like, “Oh yeah. Of course everybody should be doing this.”

Kim Lantis: Right. But it’s sort of this catch 22 or this chicken and egg effect, I think too, because I can recall, in my early, you know, young adult years, I worked in the food industry along with a lot of people. And I worked with a particular franchise and I remember at the end of the day, tons and tons of food was put in the trash – prepared food, of course, soups, biscuits, you name it. And I remember asking the manager, “Why aren’t we giving this to a homeless shelter or something of that sort?” And his answer was, “Legal reasons. Because if we give this soup to a homeless shelter and somebody gets sick, or even claims to be sick, and we are a huge company…” Right? Suing and lawsuits. So is that also something that needs to change in the food industry, the legal component of what is worthy of a lawsuit? Are we too sue-happy as a culture? Does that have to change?

Benji Koltai: Well again, I think that if you, if there’s a technology where you could prove that this dish was safe, then that would solve that problem. And the legal sort of control and protection is still valid and it doesn’t have the side effect of causing this waste because now there is a path where you can remain within the law. You can keep people safe and you can still upcycle that food and you can still prevent that food waste.

Tullio Siragusa: So to your point with traceability, with traceability comes accountability. So you reduce the risk of that happening cause you can trace back to the source of every ingredient that would probably change that risk factor.

Kim Lantis: Because also utilizing technology like Galley, in theory, that restaurant wouldn’t even have waste because they’d be able to properly project how much is going to be consumed.

Benji Koltai: Exactly.

Tullio Siragusa: This is a very big, important topic. I’m glad we’re talking about it. We’re running out of time, but we definitely want to shift and learn a little bit more about Galley itself as a company. The kind of people that get behind this sort of mission, because this is a mission. You hear a lot of companies talking about wanting to change the world, making the world a better place, and then doing little missions here and there. But this is huge in terms of the societal impact this can have. What kind of people are attracted to come work there and why?

Benji Koltai: Yeah, it’s a great question and I appreciate you asking it. We are very mission-driven. Our purpose is ultimately to align the demand and supply in the global food system. That’s what we’re doing. We ultimately want to take this 40% number and bring it down to something more like 2 – 3%. So the way we get there is this first product. This is very much our first step, is to get to the center of this data, solve it, digitize it. And then there’s the next ring of where we take technology and how we impact the food system. And so the folks who we have working for us, every one of them, really embodies that mission, that purpose. And we’re really driving to find folks who have a similar sort of idea, a skill set that can help us execute. You know, right now we’re looking for engineers, folks for customer success, sales, you know, finding the right persona that has that shared passion for reducing food waste and helping operators execute more efficiently.

Tullio Siragusa: Brilliant. I was thinking, it’d be so cool. Like you’re sitting at a restaurant ordering your food and you can actually read a story about where all the ingredients came from. Where were the grown and a little bit about the family that’s running that farm. I mean, that’s the kind of thing you could do with this sort of technology. So you can gamify it and make it fun.

Benji Koltai: Yeah. I’m really excited to be able to show a carbon score for every dish so that you can sit down and not only see a price, but you can see the carbon cost of this dish. And if you’re going to order the steak, you’ll see that that’s a higher carbon cost than if you’re going to order the plant-based meal. And so creating that data, that feedback loop, is just going to change behavior of the consumers and help to drive this positive change that we’re trying to do in the food industry.

Tullio Siragusa: Knowledge really is power.

Benji Koltai: Absolutely.

Kim Lantis: Ignorance is bliss.

Tullio Siragusa: All right. Well, it’s been great to have you with us. You guys have any final questions? We’re out of time. We could talk about this for hours, but any additional thoughts you guys?

Kim Lantis: Oh, I just want to say thank you. I thank Benji for being with us today, for your initiative. Also to Sprig for allowing you to kind of, I don’t know how that went down, but being able to carry on that internal initiative. I think that speaks a lot to company cultures as well. And just your drive and fearlessness to keep carrying the baton. Congratulations.

Benji Koltai: Awesome. I appreciate it. It’s been a really fun conversation. Really appreciate you all having me.

Tullio Siragusa: Yeah. We wish you a lot of success. Stay with us as we go off air in just a minute. This is it for the week. We’ve got next week coming up. Besides The Recap Show on Monday at 12 o’clock Pacific, what do we got coming up, Carlos?

Carlos Ponce: Three shows Tullio. We’ve got a full week ahead. And the first one on, well as you’ll know, it’s Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays at 12:00 PM Pacific. And then on Tuesday we will be speaking with Albert Saniger, the Founder and CEO of Nate. That’s the name of the company, nate.tech, “The Future of E-commerce.” And then on Wednesday we have Cenk Sidar at Enquire. And finally on Thursday we have Craig Fryar at Fundify, which is a FinTech company. So folks stay tuned for all those shows at 12:00 PM Pacific right here on dojo.live. Don’t miss them. They should be as interesting as only dojo.live interviews can get. So join us right here on dojo.live, and remember, enjoy life, have fun and be safe. Thank you.